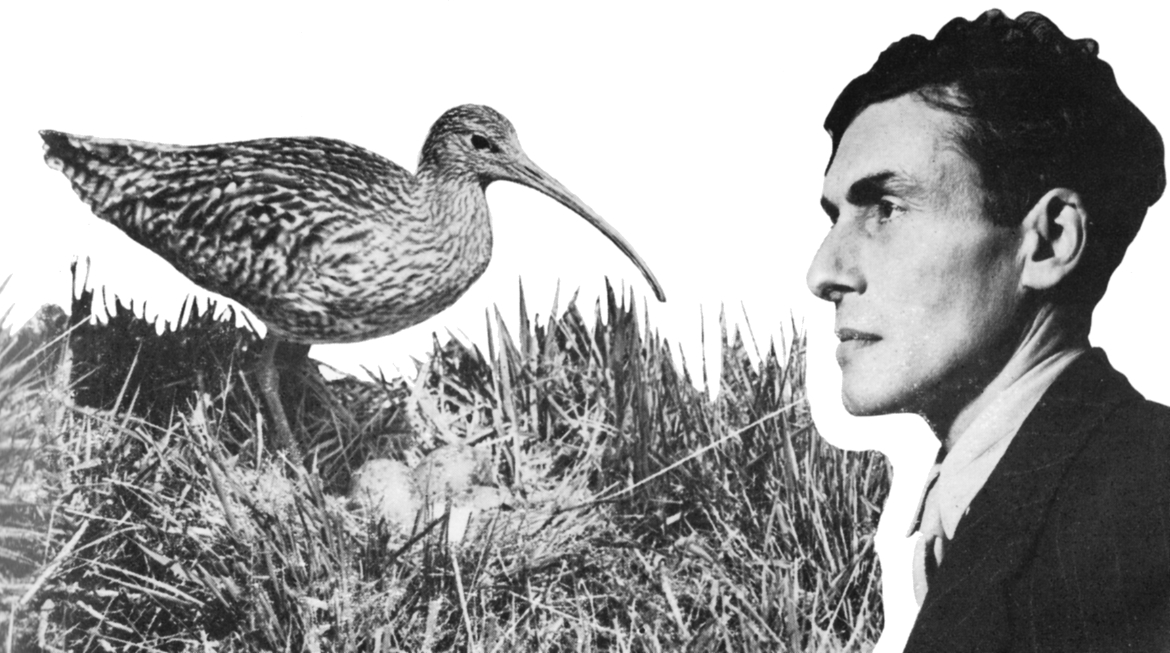

A FAVOURITE SPOT FOR WILD GEESE – At Slimbridge, Gloucestershire, Peter Scott has established the Severn Wild-fowl Trust. A world authority on wild geese, Peter Scott is heard in ‘Bird Song of the Month’ and ‘The Naturalist’ which Desmond Hawkins produces.

The contribution which each region makes to national programmes is naturally influenced by local characteristics. In the West we have not got the full-blooded music-hall traditions of the North Country or the wide industrial interests of the Midlands. Ours is primarily a rural area, famous for its magnificent scenery, its rich and varied wild life, and its pleasant country speech. West Region plays its part in every sort of programme, but it is those dealing with the countryside which are in most frequent demand — dramas of the countryside, like The Farmer’s Wife and Tess of the D’Urbervilles, and country programmes like The Naturalist and Country Questions.

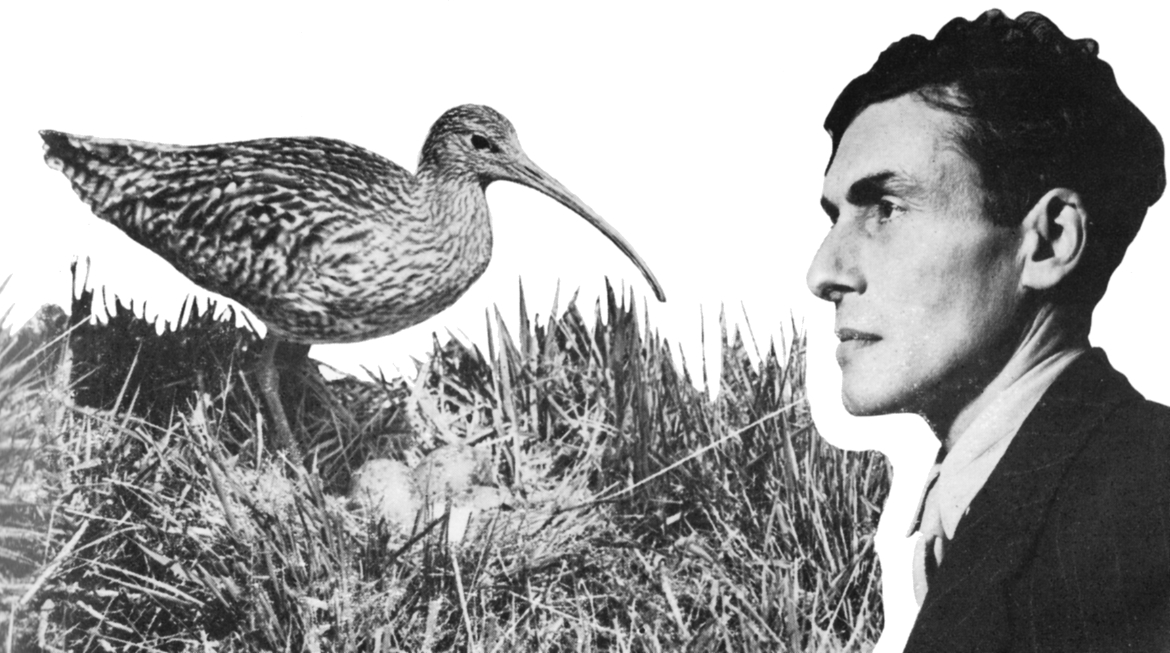

FANCY MEETING YOU – For three years the wild musical notes of the curlew have introduced each edition of ‘The Naturalist’. Desmond Hawkins says ‘It’s my favourite bird – naturally’.

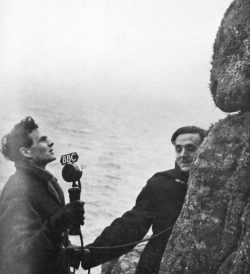

‘AND YOU CAN JUST HEAR A COCK-PHEASANT IN THE BACKGROUND’ – Ludwig Koch, whose amazing recordings are a feature of West Region nature programmes, listens critically to the day’s results.

The predominance of westcountrymen among the most popular broadcasters about the English countryside is remarkable — one thinks immediately of Ralph Wightman, A. G. Street, Brian Vesey-FitzGerald, Ralph Whitlock. It is natural therefore that most of the BBC’s main series of country and nature broadcasts come from West Region. No less than four series of this kind, with national coverage, originate from the West. The veteran among them, The Naturalist, continues an unbroken run which began three years ago and has now established itself as an authoritative voice which can hold the attention of a wide audience. With the lively and popular Country Questions and Bird Song of the Month it forms a successful trio of regional contributions to the network of Home Services. And for Light programme listeners West Region now originates a monthly nature ‘magazine’ — Out-of-Doors.

‘THE VERY FISH I WAS AFTER’ – Sir Grimwood Mears, whose commentaries by the Wiltshire Avon have become radio classics. Here he is with the man who catches the fish, Frank Sawyer.

So much then, for the scope and content of West Regional programmes. But how are they made up? What happens between the first discussion of an idea and the broadcasting of it in its completed form?

EATING OUT OF HIS HAND – Swans – and listeners – take kindly to the easy manner of Brian Vesey-FitzGerald, the BBC’s No. 1 naturalist broadcaster.

The best way to reply to that is to trace the stories of two people — let’s call them John Wood and Ruth Drake — who happen to walk up Whiteladies Road together to Bristol’s Broadcasting House. Ruth Drake is a young actress. She has had some professional repertory experience and she feels she is now well enough equipped to face the test of an audition. Mr. Wood is a man with an idea. He knows that a Wiltshire factory has just perfected a rocket capable of reaching the moon and of automatically transmitting scientific-instrument readings. The invention has been secret, but news of it is shortly to be released. Mr. Wood has come to Broadcasting House to point out that the invention and construction of this rocket — the M32 as it is called — would be a good subject for a broadcast.

‘YOU STAND ABOUT HERE’ – A tense moment for the would-be broadcaster. When she has been shown how to work to the microphone she has the attention of a panel of producers for a ten minutes’ audition.

While Mr. Wood is discussing his project, Miss Drake is having her audition. It is rather impersonal, and she is a little disappointed at not seeing any of the producers who are listening to her. A secretary explains to her what to do, and a voice from the invisible panel of producers talks to her through the studio loudspeaker. Rather impersonal — but fair and proper, because Miss Drake’s visit is not a social one and it is only her voice that matters. She performs her own selection, and is then asked to read at sight some passages handed to her; after which the voice from the loudspeaker promises that she shall have a letter within a few days. When Miss Drake departs, Mr. Wood is also leaving — with the promise that his idea will be considered for development in whatever form suits it best.

That is how the raw material of broadcasting comes to West Region. What happens next? Miss Drake gets her promised letter, and in her case it says that her audition was successful and she is therefore being added to the casting file. Let’s open the casting file and look at her card —

DRAKE, RUTH. Chewton Cottage, Queens Stanton, Somerset. No phone. Voice-age — 25-35. Pitch — mezzo. Tone — clear, warm, flexible. Normal accent — neutral. Dialects — authentic Somerset, stage cockney. Verse — no. Straight — yes. Character — no. Experience — professional rep., no broadcasting. Remarks: a fresh and pleasant personality, diction a bit untidy in emotion, no serious affectations, has attack and a well-varied range of feeling. Excellent Somerset and considered promising as straight juvenile.

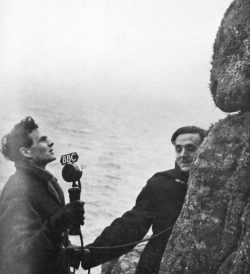

WHAT ARE THE WILD WAVES SAYING? – Plymouth’s Features Producer, Brandon Acton-Bond, goes to Land’s End with Stan Comms in search of programme material.

Having read that, let’s put it back in the file for the producers to scan when they are casting. It is Mr. Wood we want to follow now because that M32 rocket idea of his is developing fast. West Region’s Head of Programmes, Frank Gillard, has been considering various sorts of M32 broadcasts. A news item, a spot in Week in the West, a straight talk by the inventor, a documentary feature, a recording-car visit to the factory. All possible, but which shall it be? Obviously it will be a big story; the national press will report it; people everywhere will discuss it. News-cover is therefore essential on the day the rocket takes off. Apart from West Region’s own interest, other news departments will want to come in on it — London Home News, Light Programme’s Radio News Reel, Television, Overseas, and so on. West Region’s News Editor will deal with all that. In addition there ought to be a full-scale documentary beforehand, giving the whole story of what is clearly a sensational west-country achievement. Listeners will want to know the background, the personalities, the difficulties, the prospects of success, the whole dramatic context of M32. And since that will involve all the main resources of radio — and that is our only reason for inventing M32 — let’s follow the construction of that documentary programme.

First, Gillard discusses the idea with one of his producers — let’s call the producer Brian Tate — and waits to see if he ‘warms’ to it. Like most things, radio programmes can’t be done well without enthusiasm. However, Tate is impressed by the M32 story, so he and Gillard start to consider how long the programme should be and what it should cost.

Duration is settled as one hour, and it is Tate’s job to decide how to fill those sixty minutes. Shall he use ‘actuality’ voices — the voices of the people actually working on M32 — or shall he use actors? If he uses actuality shall he record them on the job, speaking spontaneously; or shall he script them and bring them to the studio where he can rehearse them? Is he to use literal sound-effects recorded in the factory? Is this a programme that wants music to heighten the dramatic effects? Professional actors will give a greater range of expression, a more gripping performance. Actuality voices will be convincingly genuine; but if they are recorded spontaneously they will be diffuse and matter-of-fact, while if they are scripted they may lose — by a woodenness of delivery — what has been gained in coherence and dramatic point. ‘Real’ noises have a treacherous way sometimes of sounding unreal or meaningless; and music, which heightens the atmosphere for one listener, may be considered a worthless intrusion by another.

Every technique has its disadvantages as well as its advantages, and some do not mix with others. However, Tate has now got to make up his mind — and for the sake of illustration let us assume that in a moment of exhilaration he decides to use as many methods as possible.

Having made those decisions, Tate goes off to the M32 factory.