During that last run Brian Tate checks his timing of the programme with a stop-watch, jots down notes of any last-minute alterations and corrections he wants to make. At the finish he is still a minute and a half over length. Cuts to make, therefore, and a final inquest on everyone’s performance. ‘Speech 8 on page 14 can go. Rex, we’ll shorten the music link there too — come out where we marked it earlier. And we must cue-in the effects more quickly — we were losing time on them.’

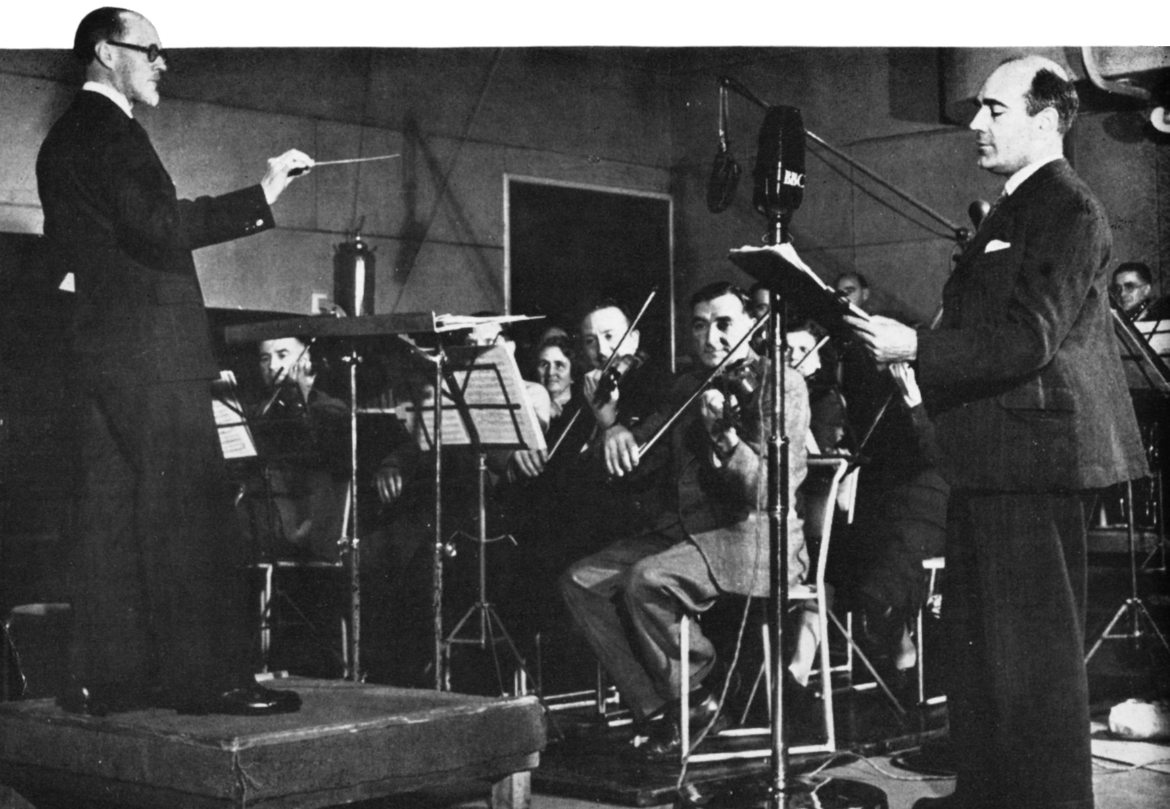

‘QUIET PLEASE’ – The red light flickers. Senior Announcer Hugh Shirreff prepares to announce the programme. Reginald Redman waits for his cus.

The crisp, clean scripts of the morning are now rumpled and scrawled with deletions, amendments, and strange hieroglyphics. Everyone is beginning to feel weary. The studio air is dry and smoky. Ruth is relieved to hear at last the words — ‘Let’s break now till transmission’. Out in the fresh air for a bit, then a meal in the canteen, a drink at the BBC club, and it is time to go back to the studio. Now for it.

‘ON POINT DUTY’ – In the announcer’s continuity studio Elsie Otley watches the flow of programmes, fills each gap, and takes over if a programme line fails. A split-second job in which every decision has to be a quick one.

Nine minutes to go. An engineer is testing the studio, checking each microphone point and plug with Control Room, watching for the flick of the red light as each link in the circuit is approved. ‘Leads at the back’, he murmurs, fingering the mike terminals. Flick. ‘Plug in the Wall.’ Flick. ‘The time by the studio clock is seven fifty-one, and eighteen seconds . . . nineteen . . . twenty . . .’ Flick. To a broadcaster that familiar ritual is as evocative as the call-boy’s ‘Overture and Beginners Please’ to an actor.

CANTEEN CONFERENCE – Across the canteen table yesterday’s programmes are discussed and tomorrow’s are debated. Celebrities from different spheres meet together: Freddy Grisewood (left) has a cup of tea with Mrs. Good, mother of the Bristol quads. Opposite them are Rosemary Colley and Hamilton Kennedy.

The last minutes tick away. Everyone is keyed up now. Tate says ‘Good luck. Enjoy yourselves. I’ll be listening,’ and retreats into the control-cubicle. Beside the green light on the studio wall a red light begins to flicker — signalling that the studio is about to become ‘live’. There is a hush, and the red light stops flickering, steadies. The announcer raises his script and leans slightly forward.

‘This is the West of England Home Service. . . .’