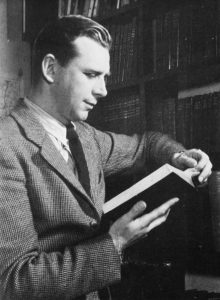

DOYEN OF REGIONAL DRAMATISTS – Eden Philpotts relaxes in his eighty-sixth year, with Sara. For the last twenty years the famous Devon playright has been an enthusiastic contributor to west-country broadcasting.

In music and in drama the West has its characteristic traditions. Writers like Thomas Hardy, Eden Philpotts, and Charles Lee speak to Dorset, to Devon, to Cornwall, with a special intimacy and understanding of local foibles. The folksongs of the West and the Cornish style of choral singing are similarly inimitable. They are only one thread of our cultural pattern, it is true, for the arts are no great respecters of frontiers; but they express something vital and unique in the make-up of west-countrymen.

During the war the resources of local culture were so uprooted and diffused, so generalized in the national pool, that the return of regional broadcasting in 1945 amounted almost to a new venture. The pre-war fabric had largely collapsed. Choirs and orchestras had disbanded, broadcasters of every kind had moved or died or lost touch. The programme staff of West Region were mainly newcomers with no pre-war recollections to guide them, so there was much to be done.

- DUDLEY SAVAGE, whose ‘As Prescribed’ programme is planned for hospital listeners.

- WINIFRED DAVEY’s mischievous accompaniments are a feature of ‘Smoking Concert’.

- A HOMELY AND UNPRETENTIOUS PROGRAMME which has caught the fancy of listeners in the region – and beyond. Francis Pope, Ronald Brickell and Harold C. Gee bring you ‘Melody for Late Evening’.

- DANCING IN STUDIO ONE to Norman Brooks and his Lancers – and the music of those Hansom Days.

A few experienced radio stalwarts were available — among actors one thinks of Phyllis Smale, George Holloway, Hedley Goodall — but in the main the first need was to make a new survey of the region’s resources; to find more actors and dramatists, singers, choirs, bands, and orchestras, whose work was up to broadcasting standards.

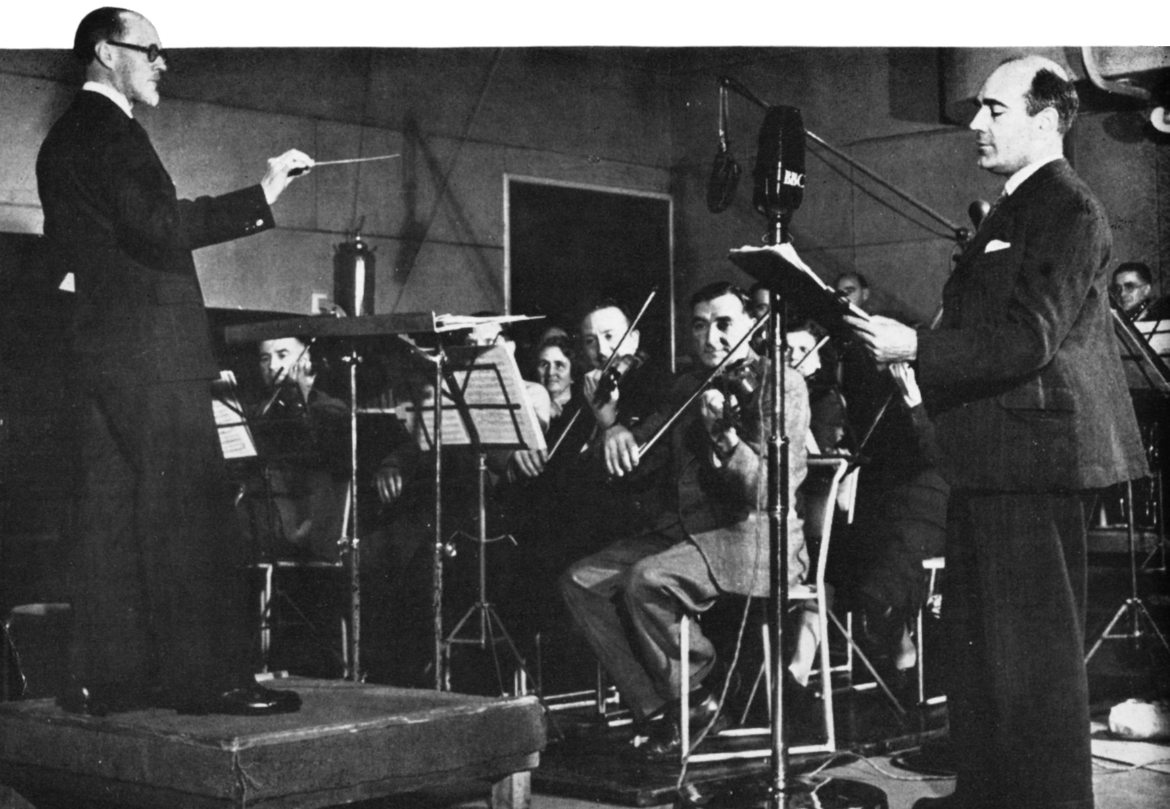

‘WHAT A CONCERT HALL SHOULD BE’ – The Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra plays under the baton of Rudolf Schwarz. Bournemouth’s Winter Gardens, in a setting of pine trees, is now the home of the West region’s premier orchestra.

This meant, of course, a great deal of auditioning. Over a hundred actors and actresses were heard in eighteen months, and about a quarter of them broadcast subsequently. In nine months over two hundred and thirty musicians and singers were heard at auditions, and thirty-five of these broadcast shortly afterwards. There was also considerable auditioning of bands, choirs, and light orchestras, and this search for new talent still, of course, goes on.

PLAN FOR ACTION – Like a general poring over maps, Rudolf Schwarz studies a score before rehearsal at Bournemouth.

Here it’s reasonable to ask why all this is necessary, when the abundance of national talent on which London draws can provide a full programme of music and plays and general entertainment. The answer is that regional broadcasting has the obligation to foster local talent for two reasons: because the opportunities it offers can resist the draining into London of provincial talent (and the consequent impoverishment of local life), and because each region is best fitted to provide its own distinctive style of performance. To present the works of Charles Lee and Eden Philpotts in anything but the Cornish and Devon dialects respectively would be to rob them of their essential quality (and incidentally to foment an uprising in Cornwall and Devon!) The resources of the professional stage in London cannot provide authentic casting in such cases as these and the many other regional dialects which lend diversity and richness to our language throughout the United Kingdom. Again, it is not enough to have thousands of music-lovers dependent on the occasional visits of London orchestras, and the enterprise of the Bournemouth Municipality in forming a first-rate resident orchestra is a fine example of the sort of activity West Region should — and does — support. The primacy of London as the focus of our national culture is indisputable and right; but it has been becoming too strong a magnet. One of the proudest objectives of regional broadcasting is to restore vigour and abundance and exacting standards to local forms of culture. The formation and training of the West Country Studio Orchestra and the West Country Singers are two achievements which show what can be done.